Controversial_Ideas , 4(1), 3; doi:10.35995/jci04010003

Article

Islamist Extremism in Australia: Tracing the Ideological Roots and Pathways to Radicalisation

How to Cite: Satterley, S. Islamist Extremism in Australia: Forming Beliefs and Religiosity on the Trail to Jihad. Controversial Ideas 2024, 4(1), 3; doi:10.35995/jci04010003.

Received: 18 October 2022 / Accepted: 5 April 2024 / Published: 29 April 2024

Abstract

:Australia has not been immune from patterns of recruitment, attacks and foreign fighters harbouring the ideology of Islamist-jihadism. This paper draws on sociological data from a nationwide survey of 1034 Muslim Australians to analyse the way in which pathways to knowledge exist for Muslim Australians in relation to interpretations of Islam and, importantly, the adoption of an Islamist or Militant interpretation. Islamist and Militant typologies will be examined to see if their sources of Islamic influence were different or the same in their belief formation compared with more moderate typologies. This paper will also examine those participants who indicated that the Quran should be read literally and analyse the overall religiosity of the various typologies, with the aim to get a sense of the connection between (moral/ethical) belief formation and daily ritual of Islamists and Militants. This paper finds that Muslim Australians categorised as Political Islamist and Militant are more likely to have been influenced by mainstream areas of Islamic knowledge and discourse, such as the Quran, hadith, ulema, and the mosque, whilst also interpreting the Quran literally and praying daily. These findings suggest a challenging path forward for counterterrorism and countering violent extremism policies and programs in Australia.

Keywords:

Islamism; jihadism; religiosity; Australia; Muslim Australians; terrorismIntroduction

In 2014 the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) promptly and violently took over large parts of the Levant. The following years saw tens of thousands of fighters and supporters from all around the world leave their homes and go join this new caliphate. Over a decade earlier, the events of September 11, 2001, were traditionally the first reference point for scholars of terrorism; it is usually the first factor mentioned to show the scale of the contemporary threat of terrorism that states may face. Due to the shocking images and magnitude of the September 11, 2001 events, this is unsurprising; however, over a decade later what we have witnessed with a group like ISIS is arguably more shocking. This is because so many ostensibly bright, educated, and motivated Muslims would be willing to join this violent terrorist/insurgent group. Krueger (2018) argues that there is little direct link between poverty, education, and participation in terrorism by groups like ISIS. Instead, the data point to terrorists often coming from relatively advantaged backgrounds, in contrast to the common criminal profile.1 What is clear however, is that underlying ideology that led to the hijacking of planes in 2001 was still fully operational 15 years later and continues to be. More recently (2020) the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) has noted that Australia’s threat level remains “PROBABLE” and that the “we have credible intelligence that there are individuals in Australia with the intent and capability to conduct an act of terrorism. Religiously motivated violent extremists want to kill Australians. Groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) continue to urge attacks”.2

This paper attempts to examine the “religiously motivated aspect” to which the ASIO Annual Report is referring by highlighting how those who are more inclined to an Islamist or jihadist ideological worldview construct and/or justify their Islamic religious identity. The question is: Are those Muslim Australians more or less likely to draw influence from religion in order to construct and/or justify an Islamist or jihadist ideological worldview? By asking this sociological question this paper will attempt to highlight some Durkheimian social facts regarding Islamist extremism (in Australia). In a recent paper, Dawson lamented the fact that within the social scientific study of religious terrorism there is an “erasure of religiosity as a significant motivational factor” and that this peculiar interpretive preference, is “methodologically unsound and theoretically and empirically unhelpful”.3 Whilst recognising Dawson’s point, this paper will show that when defining Islamism one can see the intrinsic link between religion and extremism but also recognise that this link is often deemphasised. This paper will add to the discussion outlined by Dawson by examining sources of Islamic influence, interpretation of the Quran, and religiosity of Muslim Australians that show an affinity towards Islamist or Islamist-jihadist interpretations of Islam. By examining the participants that showed this Islamist ideological affinity, we can then make a comparison with those who did not, to analyse exactly where the differences lie in sources of Islamic influence and religiosity (we will explore why religiosity is important, too). This paper will conclude by providing a list of overall findings regarding belief formation and Islamism in Australia and policy recommendations for countering violent extremism in Australia.

Radicalisation Literature

Attempting to mitigate the ideology of Islamist-jihadism requires a sophisticated understanding of how individuals encounter it, to then find it appealing. Many models and theories that define and describe the process of radicalisation to violent extremism traditionally contain ideology as a (or the) critical factor.4 Radicalisation is a contested term but is generally defined as a process by which individuals or groups become more extreme or radical in their views.5 Mandel puts forward this definition: “Radicalisation refers to an increase in and/or reinforcing of extremism in the thinking, sentiments, and/or behaviour of individuals and/or groups of individuals”.6 Another definition, by Precht, proposes that for it to be radicalisation, the individual or group must be looking to affect changes in society.7 The changes in society depend largely on the ideology that the individual adopts but usually consist of a combination of political/religious activism which can be expressed in various ways. Keeping these definitions in mind, we will notice how Islamism meets these definitions of radicalisation and thus note the connection of religion and radicalisation.

However, radicalisation as a concept has expanded, so it is important to avoid a naïve and oversimplified understanding that it is merely the result of indoctrination to specific ideological beliefs. Scholars have moved to show the complexity of the process by highlighting “multiple other psychological, socio-psychological and sociological factors.8 Scholars such as Moghaddam, Wiktorowicz, Sageman, and Crone have brought our knowledge of the process of radicalisation forward by highlighting how much more sophisticated our understanding needs to be.9,10,11,12 However, as Dawson contends, “with few exceptions, the new perspectives displayed a tendency to overcompensate for the earlier reliance on the simple internalization of beliefs by minimizing the role of ideology (and hence religion) altogether. In most cases, this involved emphasizing the importance of social-psychological processes, as delineated by social identity theory for example, while explicitly stating that the influence of ideological factors is secondary”.13 The author has argued elsewhere that sociological and psychological factors play a critical role in the radicalisation to Islamist extremism in Australia.14 The author has argued that these include personality traits and moral intuitions as highlighted by Gambetta and Hertog and Haidt’s moral foundations theory respectively.15,16 Thus, whilst not devaluing other factors, this paper seeks to consider where less emphasis has often been given to studying the religious sources of influence for Islamist and jihadists and how this relates to their ideology. This is not to give the impression that studying and emphasising the religious factor in Islamic terrorism is largely missing from the literature; authors such as Jones, Wood, Harris, and Ballen have shown us just how much influence jihadists draw from notions of the divine, paradise and martyrdom which will be discussed more below.17,18,19,20 Jones in particular, developed a conceptual model of religious terrorism from a psychological perspective which explains how shame, guilt and humiliation and the separation of the world into good and evil with a punitive, yet perfect deity sometimes requires the shedding of blood, noting that support for all these beliefs can be produced by selective emphasis on aspects of a sacred text or the particular religious tradition. This link between religion and radicalisation that will be explored – as we will see when discussing and defining Islamism and jihadism below – for Muslim extremists Islamism is their religion, and espousing this worldview is a form of radicalisation under most definitions.

Method

This paper will analyse the way in which pathways to knowledge exist for Muslim Australians in relation to interpretations of Islam and importantly to the adoption of an Islamist interpretation. This paper draws on previously published data from a nationwide survey of 1034 Muslim Australians (citizens or permanent residents) conducted between September and October 2019.21 The survey consisted of over 150 questions, including two preliminary eligibility questions, 13 demographic questions, approximately 20 convert-specific questions, and approximately 130 main questions. Likert scales were used to measure respondents’ agreement/disagreement in relation to various statements, as well as several open-ended questions. The survey instrument was fielded online using Lime Survey and answering questions was mandatory in order to proceed to the next section, so as to avoid missing values. The survey was conducted in English only and disseminated online with the support of Muslim community organisations, groups, and individuals around Australia who shared the link to the survey through email and across social media platforms, particularly Facebook. The 1034 Muslim Australian citizens and permanent residents who completed the “Islam in Australia” survey were representative of the Muslim Australian population in relation to a number of demographic indicators.22 This paper will utilise questions asked within the survey that were designed to assess the most influential Islamic sources of knowledge for participants.23

Our analysis starts by examining what sources are the most influential for participants in their current understanding of Islam. This will be done with reference to the various typologies of Muslim Australians generated within the survey findings, allowing us to see if those participants categorised in the Islamist and Militant24 typologies had viewpoints that were different or the same in their formation of Islamic/Islamist beliefs. Following this, we will look at those participants who indicated that the Quran should be read literally and at the overall religiosity of the various typologies, with the aim to get a sense of the connection between (moral/ethical) belief formation and daily ritual. Again, this will allow us to examine how these beliefs were constructed in relation to Islamism, at least compared with other ways of interpreting and practising Islam.

Before examining the sources of influence, it is instructive to note that participants within the “Islam in Australia” survey were categorised into 10 typologies. Participants could agree with the following statements and were subsequently placed into the following typologies:

- Cultural nominalist: “I am a cultural Muslim for whom Islam is based on my family background rather than my practice.”

- Secular: “For me Islam is a matter of personal faith rather than a public identity.”

- Liberal: “I believe Islam aligns with human rights, civil liberties and democracy.”

- Sufi: “I am a devout Muslim who follows a more spiritual path rather than formal legal rules.”

- Ethical-Maqasidi: “I am a committed, reform-minded Muslim who emphasizes the spirit and ethical principles of Islam over literal interpretations.”

- Progressive: “I am a committed Muslim who believes in the rational, cosmopolitan nature of the Islamic tradition based on principles of social justice, gender justice and religious pluralism.”

- Traditionalist: “I am a devout Muslim who follows a traditional understanding of Islam.”

- Legalist: “I am a strict Muslim who follows Islam according to the laws of sharia.”

- Political Islamist: “I am a committed Muslim who believes politics is part of Islam and advocates for an Islamic state based on sharia laws.”

- Militant: “I am a committed Muslim who believes an Islamic political order and sharia should be implemented by force if necessary.”

Those that agreed or strongly agreed with the statements categorised as Political Islamist and Militant are particularly seminal for the purposes of this paper. These two typologies were generated through reviewing the literature on Islamism, which is a complicated and contested term; some scholars even go as far to express their desire to not use it, or only use it with specific caveats, usually in relation to its broad and sweeping use or pejorative framing.25 Analysing Islamism begins to get complicated and even controversial when one digs deeper into exactly what the foundational beliefs for the ideology/individual are. Islamism of course has a connection to Islam but just as there are Islamisms, there are also Islams and it may be “practically impossible to identify the ‘real message’ of Islam”.26 Whilst this point might not be recognised by many Muslims, it is nevertheless true that Islam can be and is interpreted and practised differently by practically all Muslims around the world. However, this is not to say that typologies, or general trends of shared characteristics (beliefs/practices) do not exist, or that group, community, or state characteristics do not surface; on the contrary, scholars such as Fattah and Duderija and Rane take steps in identifying such typologies.27,28 Furthermore, given the doctrine of Islam, beginning with the Quran and the hadith and the subsequent classical and contemporary interpretations, particular beliefs are more or less likely to be observed.

Unfortunately gaining conceptual clarity is very challenging when one analyses the Islam/Islamism distinction. Mozaffari has perhaps made the useful progress in this area, using this definition of Islamism: “a religious ideology with a holistic interpretation of Islam whose final aim is the conquest of the world by all means”.29 It is instructive to note that most definitions of ‘ideology’ consist of a dogmatic system of ideas and beliefs connected to, most importantly, a political theory.30 Mozaffari explained specifically how Islamism is an ideology:

Islamists pick up some elements in Islam and turn them into an ideological precept. Islamism indeed fulfils all requirements of an ideology, but it goes beyond the purely ideological dimension and sacralises the very essence of ideology. Therefore, Islamism differs on this point from other totalitarian ideologies as it takes its legitimacy from a double source: ideology and religion. Owing to its double character, actions undertaken by Islamists are seen by them as religious duties. Where a Nazi feels responsible to his Führer, an Islamist is responsible to his Leader and before Allah”.31

Mozaffari stated that rather than merely narrow theological belief, private prayer, and ritual worship, Islamism “serves as a total way of life with guidance for political, economic and social behaviour”.32 Note the connection of religion and radicalisation here, which provides us some context now that we have defined radicalisation and Islamism.

Thus, agreement with survey questions that asked participants if their interpretation of Islam is more activist and outward-looking and/or if it involves imposing an interpretation of Islam over the rest of society by force is how this paper and the survey instrument categorised an Islamist or Militant whilst acknowledging that acting upon these ideas is different than merely holding them. The Militant typology is, of course, another Islamist category where participants expressed a further belief that, if necessary, Islam and sharia should be implemented by force. It should be noted that the Militant category has the assumption that Islam and sharia are not already implemented by force, such as in places like Saudi Arabia and Iran. It is possible that a participant had these examples in mind when answering and therefore this shows support for Islamic authoritarianism rather than a non-state militant or jihadist worldview. Participants could agree to as many typologies as they saw fit and thus there was overlap between the categories. Participants were only provided with the statements to which they should agree or disagree, and not the typology label.

Sources of Islamic Influence and Understanding

The question that was asked within the survey that will assist in giving a tool for examining the belief formation of participants was: “How influential are the following sources for your current understanding of Islam?” Participants were asked to indicate one of the following four: Very influentia; Somewhat influential; Not very influential; Not at all influential. Table 1 shows the percentages of those who selected “Very influential” within each of the typologies defined in the previous section, in relation to family, imams/sheikhs/ulema, mosque/madrassa, academic scholars, Quran, hadith, and the Internet.33

Table 1.

Typologies and Sources of Islamic Influence

| Cul. | Sec. | Lib. | Sufi | Eth. | Pro. | Trad. | Leg. | Pol. | Mil. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | 38.5% | 28.9% | 30.3% | 32.1% | 28.7% | 29.2% | 33.1% | 34.7% | 35.3% | 39.5% |

| Imams, sheikhs, ulema | 19.8% | 22.4% | 30.0% | 30.4% | 26.2% | 28.0% | 38.8% | 44.5% | 44.9% | 53.0% |

| Mosque, madrassa | 18.1% | 17.9% | 22.1% | 23.8% | 20.1% | 20.1% | 29.1% | 32.9% | 34.4% | 39.5% |

| Academic scholars | 14.0% | 17.6% | 23.4% | 25.7% | 22.8% | 23.6% | 25.0% | 30.0% | 33.4% | 30.8% |

| Quran | 67.2% | 79.1% | 84.3% | 83.8% | 80.4% | 82.4% | 91.4% | 94.8% | 90.3% | 92.5% |

| Hadith | 48.5% | 58.6% | 68.3% | 63.8% | 60.6% | 65.2% | 80.8% | 87.3% | 83.9% | 87.6% |

| Internet | 18.1% | 15.1% | 17.1% | 17.6% | 16.0% | 16.9% | 20.2% | 20.4% | 25.2% | 25.9% |

Family

The influence of the family in relation to Islamists and jihadists, whether as an alternate sense of belonging or as an influence in one’s radicalisation, is a common factor when we look at various groups and terrorist attacks. Family is often an important element in the radicalisation process; often a drifter or misfit might be looking for a sense of belonging to a family that he or she never had or had had a breakdown with, or might just simply be looking to create a new identity for themselves.34 Many religiously extreme groups like cults explicitly talk about being a family.35 Biological families also feature commonly among recruits to Islamist/jihadist groups. Examples are, the brothers who attacked the Boston marathon in the US in 2013, the brothers and families involved in the Sri Lankan attacks in 2019, the Jamel brothers in Australia (three have been arrested for involvement with terrorism), and many other instances of siblings and other family members recruiting amongst themselves.36 The salience of romantic and comradely love can also often be seen in recruitment to extremist groups.37

Within the whole sample of 1034 survey participants, 294 (28.3 percent) indicated that family was “very influential” for their current understanding of Islam. What is noticeable first within the table is those who agreed with the Cultural-Nominalist typology over many other typologies in relation to the family influence. However, what is also noticeable is the proportional increases with regards to the Legalist, Political Islamist, and Militant typologies and the influence of the family. This appears to confirm the importance of the family in relation to the dissemination of Islamist memes but also that, at least in regard to how beliefs how formed, Islamists gain influence from the family unit.

Imams/Sheikhs/Ulema

Saudi Arabia has been very successful at transporting its conservative, rigid, and destabilising interpretation of Islam, particularly since the 1960s.38 This has led to the contemporary proliferation of Islamist and jihadist groups around the world.39 The funding of Islamic institutions has, of course, meant funding for ulema who are willing to promote the Salafi/Wahhabi Islamic narrative.40 This context may explain, in part, why extremism may find a home within Sunni communities which make up the majority sect in Australia, but it does not explain extremism within Shia communities where Shanahan has noted that Lebanese Shia make up 40 percent of the country of origin background of known Australian jihadis.41 Whilst we do not know the content of the Islamic teachings from the survey findings, the findings will indicate if the more Islamist and illiberal typologies are drawing influence from religious leadership. Therefore, we can start to examine if Australia appears to have any destabilising religious subtext emanating from religious leadership that we see elsewhere around the world.42

For the whole sample, 309 participants (proportionally 29.7 percent) indicated that the imams/sheikhs/ulema were “very influential” in their current understanding of Islam. Perhaps unsurprisingly a significant minority of Muslim Australians appear to be influenced by religious authorities. One would assume that these religious authorities are local/domestic, but we cannot say that for sure. It is possible that religious sermons, lectures, or talks may have been viewed online or that there has been travel involved. Looking at Table 1, we can see that the Cultural-Nominalists (19.8 percent) and Secularists (22.4 percent) proportionally sit lower than the other typologies and much lower than the average. The Liberal, Sufi, Ethical-Maqasidi, and Progressive typologies sit around the average, but when we examine the Traditionalists (38.8 percent), Legalists (44.5 percent), Political Islamists (44.9 percent) and Militants (53.0 percent), we see these proportional percentages rise strikingly in these more conservative and Islamist typologies. Quite alarmingly we notice that a majority of those who agreed with the Militant typology described imams/sheikhs/ulema as very influential. Thus, it appears that in relation to forming Islamist beliefs the influence of Islamic theological leadership for Muslim Australians who have a traditional, legalist, and in particular an Islamist/Militant interpretation of Islam is high. One way we can see if this issue is more local in origin is to look at the influence of the mosque.

Mosque/Madrassa Classes

Like the religious leadership, the mosque has been influenced by the same international factors as outlined above. The Saudi influence has undoubtedly had a large global impact on sermons as well as the madrassa curriculum. It has been argued that the teaching of Islam in the madrassa does not involve any focus on critical thinking but rather promotes rote memorisation and is therefore more conducive to the more “black and white”, rigid and Islamist interpretations of Islam.43 The Arab Human Development Report of 2003 noted that “curricula taught in Arab countries seem to encourage submission, obedience, subordination and compliance, rather than free critical thought”.44 Therefore, one would expect these types of pedagogical structures to be playing a role even in Australia, but does that necessarily translate to a more Islamist interpretation of Islam? European research has shown that the most radical Muslims in a Danish context were much more likely to have drawn influence from imams and the mosque – 60.3 percent as compared to the least radical Danish Muslims at 20.7 percent.45 Let us examine the Australian data.

From the whole sample, 220 participants indicated that the mosque/madrassa classes were “very influential” which was proportionally 21.1 percent. Given that this is lower than those who indicated that imams/sheikhs/ulema were very influential, it perhaps indicates the practice of seeking of religious authority outside of the mosque, as previously noted. Nevertheless, we can see that just over one in five participants gained significant Islamic knowledge from the mosque or the madrassa. Within Table 1 we see the influence is less with the Cultural-Nominalists (18.1 percent) and Secularists (17.9 percent). Again however, when we look at the Traditionalists (29.1 percent), Legalists (32.9 percent), Political Islamists (34.4 percent), and Militants (39.5 percent) we notice considerable increases in the influence of the mosque/madrassa. Like the influence of imams/sheikhs/ulema, the more conservative, strict, and Islamist the participant, the more likely is the mosque/madrassa to have been indicated as being very influential. Perhaps encouragingly these proportional percentages were not quite as high as the imams/sheikhs/ulema, which may indicate that Australian mosques are not preaching Islamist interpretations as much as Islamic leaders overseas or online. However, the fact that the highest proportional percentage was again in the category of Militant should give us pause and suggests we should ask: “Exactly what is being taught in Australian mosques and madrassa classes?”

Academic Scholars

For the whole sample, 229 participants indicated that academic scholars were “very influential” in their current understanding of Islam, which was proportionally 22.0 percent. Thus, as we can see, almost a quarter of all participants indicated that their Islamic understanding was heavily influenced by academia. Those who agreed with the Cultural-Nominalists (14.0 percent) and the Secularists (17.6 percent) drop noticeably below the average for the whole sample, whilst the Legalist (30.0 precent), the Political Islamist (33.4 percent) and the Militant (30.8 percent) rise noticeably above the average. The obvious question that comes to mind given these findings is what academics are the Sufis influence by compared with the more Islamist and illiberal typologies of the Legalist, Political Islamist, and Militant?

Quran

As will be shown below, Islamists within the sample are more likely to indicate that the Quran should be read literally. Reading any religious text literally as opposed to taking a more nuanced and contextual approach is often associated with fundamentalism and extremism. Therefore, we should expect to see the Quran as being highly influential in relation to the more conservative and rigid typologies. Given the centrality of the Quran in the Islamic belief system it is perhaps unsurprising that 853 participants, or 82.1 percent, within the entire sample indicated that the Quran was “very influential” in their current understanding of Islam. Those who were much less likely to indicate the influence of the Quran were the Cultural-Nominalists at 67.2 percent and slightly less likely were the Secularists at 79.1 percent. Again, the same trend was recorded, many typologies remaining around the average except for the considerably rise in proportions of the Traditionalists (91.4 percent), the Legalists (94.8 percent), the Political Islamists (90.3 percent) and the Militants (92.5 percent).

The Quran is cited by all typologies as the most influential source in their current understanding of Islam; thus even whilst the more rigid and Islamist interpretations were more likely to be very influenced by the Quran, even those that agreed with the Liberal and Progressive typologies sat very high in relation to the Quran being a strong influence. Fuller has a possible explanation for this, contending that liberal Islamists who promote the idea of democracy and freedom for the individual to choose how to interpret and understand Islamic doctrine, are then met with fundamentalist Islamists. The latter believe the path is already laid out and that there is no room for doubts or opinions on matters of morality and ethics, and they wish to compel others of this rigid worldview.46 The reason for these contradictory Islamic/Islamist worldviews is that both viewpoints can be amply backed by quotations from the Quran and the hadith.

Hadith

The hadith is a collection of writings that outlines the words and actions of Muhammad, who for Muslims is believed to be the prophetic founder of the religion. Boutz notes how the body of hadith has historically served as a bridge of authority from past to present, linking later individuals and groups to the legacy of Muhammad.47 In the Arabic-speaking community, the hadith is often used to bolster the authority of the speaker or writer in a religious or non-religious context; therefore it would be unusual if Islamist or jihadist contentions did not make use of it. The content of the hadith is extensive and surrounds topics such as ethics, morality, law, and the nature of God. Given just how vast and extensive the writings are, it has been argued that a link can be found for those with extremist views and the wide application of hadith.48 Boutz has also argued that the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) will use hadith to justify specific positions or to show religious commitment and add legitimacy to their propaganda materials. Let us examine how Muslim Australians in the survey think of the hadith as a religious influence.

Within the whole sample, 687 of the 1034 participants indicated that the hadith was “very influential” which was proportionally 66.1 percent. As we can see the hadith is very important as a source of religious influence for Muslim Australians even whilst it does not rise to the level of influence as the Quran itself. When we examine the typologies within the table, we notice the Cultural-Nominalists (48.5 percent) were much less likely to indicate the hadith as very influential and the Secularists (58.6 percent) were also less likely. The Liberals (68.3 percent), the Sufis (63.8 percent), and the Progressives (65.2 percent) all sit around the average whilst those who agreed with the Ethical-Maqasidi (60.6 percent) typology were less likely to indicate the hadith as very influential. When we look at the Traditionalists (80.8 percent), the Legalists (87.3 percent), the Political Islamists (83.9 percent), and the Militants (87.6 percent) we notice that all rise considerably when indicating that the hadith is very influential in their current understanding of Islam. It is interesting to note that the Legalists, Political Islamists, and Militants indicated that the hadith is even more influential than the average participant when asked about the Quran (82.1 percent). This is a rather striking finding and appears to support the aforementioned Williams contention that a link can be found among those with extremist views and a wide application of hadith.

The Internet

One of the most important contemporary methods for gaining access to and engaging with an ideological narrative is online. Sageman contends that the jihadist threat now comes from radicalised individuals that have most likely never been to a terrorist training camp and do not answer to leaders like Osama bin Laden, but instead are radicalised and recruited through the Internet.49 Radicalisation and recruitment material used to be physical pamphlets and VHS video cassettes; now a PDF such as Dabiq magazine (and the more recent Rumiyah magazine), YouTube clips, and social media help to facilitate Islamism and jihadism. Younger ideologues who have grown up with the Internet have been able to take full advantage of its utility, as we saw with ISIS who have taken online media production to a level of professionalism that would be the envy of many publishers. This new social and ideological environment is the contemporary space for radicalisation and recruitment.50 For Western-based diasporas the Internet is the best way to acquire information about international conflicts and there is evidence that they seek online propaganda more than even those in the Middle East North Africa region.51 However, how does the Internet compare to other influences in understanding Islam for our sample of Muslim Australians?

From the entire sample, 173 participants (proportionally 16.6 percent) indicated that the Internet was “very influential” in their current understanding of Islam. As we can see, the Internet was not a large influence for participants and within the table of typologies we notice that there are not the large disparities between the different categories that we can see in some of the other questions. Most typologies sit around the average proportion of the entire sample although the Traditionalists (20.2 percent), the Legalists (20.4 percent), the Political Islamists (25.2 percent) and the Militants (25.9 percent) did indicate a higher influence of the Internet in their Islamic understanding. The Internet may be seen more as a tool for social connection and the transmission of ideas rather than a source of Islamic knowledge.

Interpretation of the Quran

We turn now to look at the Quran more closely. As we saw above, the Quran is the most important source when it comes to the construction of an Islamic belief system. No other source consistently ranked as high as the Quran for all typologies. The Quran is the foundation, for Muslim Australians as it believed to be the word of God and therefore the way in which knowledge can be acquired is to refer to the Quran for issues of worship, ritual, daily practice, morality, and ethics.

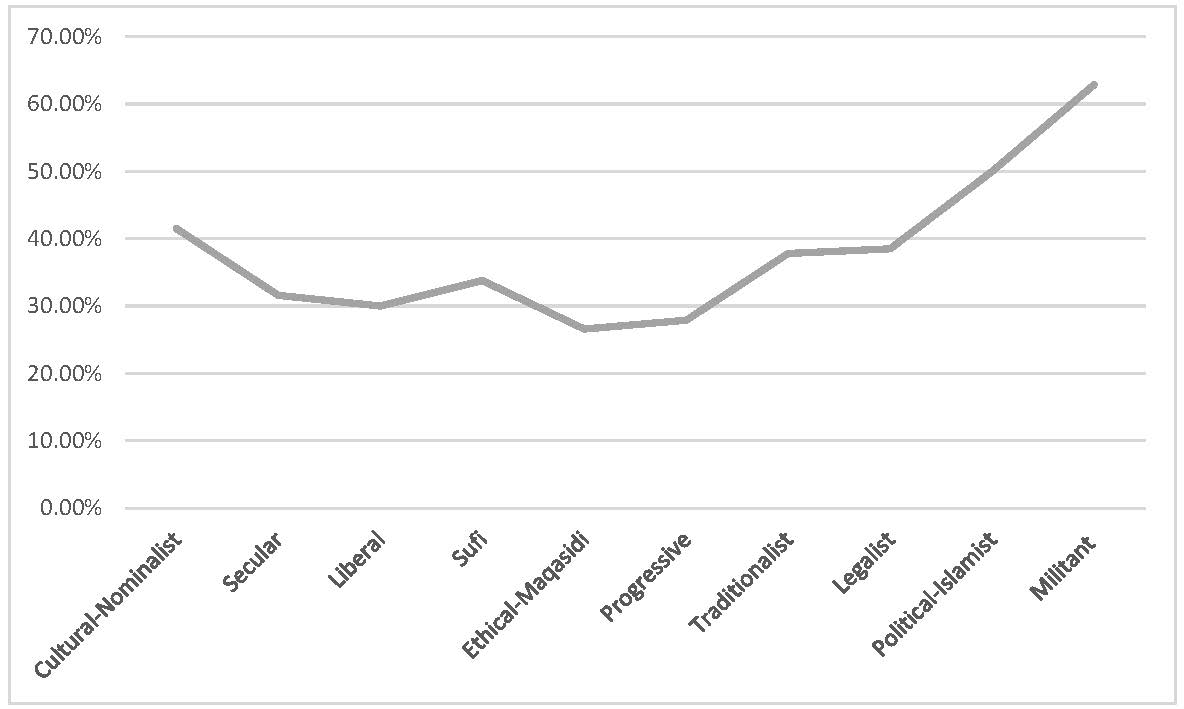

When asked how the Quran should be interpreted, 29.6 percent of Muslim Australians surveyed, agreed, or strongly agreed that this process should be done “literally”. Thus, for a significant minority the words in the Quran do not need to be contextualised or undergo any other process that may alter what the text apparently says and prescribes. One way we can examine this process further is to look at which typologies were more likely to agree or strongly agree that interpreting the Quran should be done literally. Figure 1 outlines the various typologies and compares them with participants who had a literal interpretation of the Quran. What is first apparent is how much more likely the Cultural-Nominalists (41.5 percent) were to indicate that the Quran should be read literally and following the trend of many of the findings above, the Traditionalists (37.8 percent) and the Legalists (38.5 percent) were the other typologies to rise above the average. However, most notably the Political Islamists (50.0 percent) and the Militants (62.9 percent) rose considerably higher than the average proportional percent of 29.6 percent.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Survey Respondents by Typology Agreeing the Quran Should Be Interpreted Literally.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Survey Respondents by Typology Agreeing the Quran Should Be Interpreted Literally.

These findings suggest that a literal approach to the Quran leads to a more conservative, political and Islamist interpretation. However, it is not always straightforward. Even the jihadist ideologue Sayyid Qutb disagreed with Wahhabi ulema on the reading of the Quran. For example, the Quranic verse which describes God sitting on a throne is taken literally by the Wahhabi ulema and fellow fundamentalists; however, for Qutb this verse was a metaphor for God’s hegemony over all creation.52 Remember that Qutb was a central figure in 20th-century Islamism and jihadism, which shows again that the doctrine can be quoted to support differing, even antithetical theological positions, whilst at the same time a literal interpretation appears to trend towards more conservative, Islamist, and militant interpretations. It is instructive to note that the Cultural-Nominalists sat considerably higher than the average. Remember that these participants were the least religious of the typologies, considering Islam more of a family background rather than a daily practice, but they are nevertheless more likely to say that the Quran should be read literally. This perhaps indicates that these participants notice that a literal interpretation leads to conservative Islamist and militant interpretations which is contrary to their worldview and is thus rejected. In other words, they are expressing the dangers of reading the doctrine literally.

Moral Belief Formation, Religiosity, and Prayer

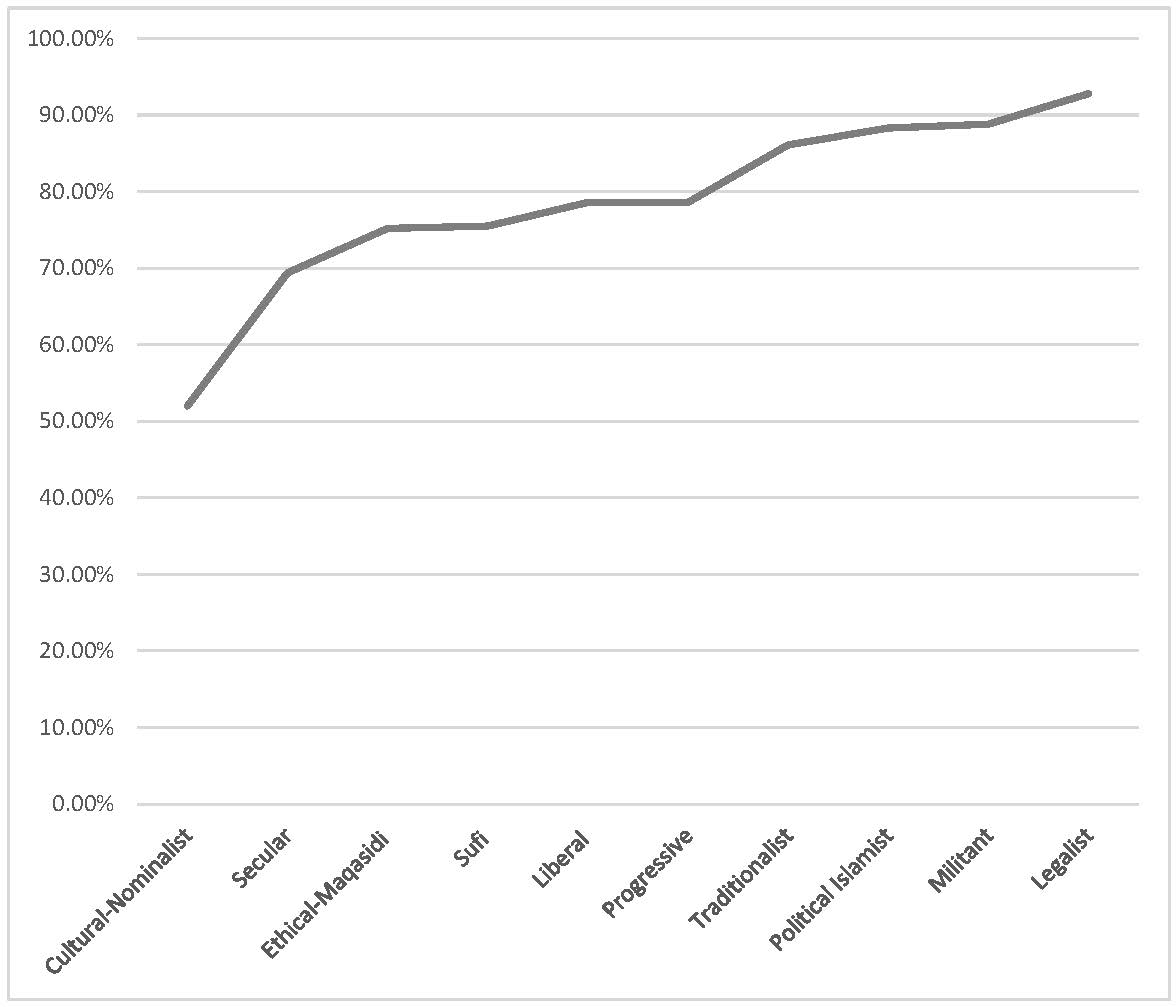

Venkatraman contends that “extreme Quranic and Revivalist interpretations ensure the ideological persistence of Islamic terrorism as a religious effort to preserve the will of God in an Islamic community”.53 Knowing what a deity prescribes and acting accordingly is a way in which beliefs and actions are justified for the religiously minded. We have already seen that the Quran, hadith, ulema, and the mosque are more influential to Islamist interpretations of Islam when compared with other interpretations/typologies. Do Islamists believe in a personal deity that not only authored the founding doctrine but continues to inform and guide? One way to assess if participants believe they are in a relationship with a personal deity in their religious practice is to examine how often they pray and examine where those with an Islamist interpretation sit in relation to other typologies. Prayer is a “central form” of religious practice along with worshipping in general.54 To preserve the will of an omniscient deity and to believe one is in relationship with that deity is conceptually considered as divine command theory. Divine command theory as Danaher explains is “a label that can attach to a family of metaethical theories, each of which is concerned with accounting for, explaining or grounding the existence of one or more species of moral fact by reference to God’s commands”.55 Prayer is, of course, one of the five pillars of Islam and thus central to God’s commands, and knowing how often a person prays provides insight into the moral and ethical belief formation of participants and is an indication of overall religiosity. Figure 2 gives the breakdown of those that indicated they “pray daily” and the typology to which they agreed or strongly agreed.56 For the whole sample of participants, 797 (76.7 percent) selected “daily” when asked how often they pray. This indicates a high level of religiosity among all participants.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Survey Respondents by Typology Agreeing They Pray Daily.

Examining Figure 2 we notice that those for whom Islam is based on family background rather than religious practice, the Cultural-Nominalists, indicated they are the least likely to pray daily, at 52.0 percent. This is unsurprising as the typology itself divorces religious practice from the way in which the participant conceptualises him or herself as Muslim and further evidences the contention made above in relation to a literal interpretation of the Quran. Those that indicated Secular were also less likely (69.4 percent) to pray daily compared with the other typologies and the average percentage. Looking at the Progressive (78.6 percent), Ethical-Maqasidi (75.2 percent), Sufi (75.5 percent), and Liberal (78.6 percent) typologies we see that these fall around the average for the whole sample. The last four typologies are the highest proportionally recorded: the Traditionalist (86.1 percent), the Legalist (92.8 percent), the Political Islamist (88.3 precent) and the Militant (88.8 percent). Note that when just including just the “strongly agrees” in relation to the Militant typology and praying daily the Militants are the highest proportion at 97.1 percent.57

As mentioned, 76.7 percent of the whole sample indicated they pray daily, which suggests a high level of religiosity among a large majority of participants. However, as we can see it is the more rigid, strict, conservative, political, and illiberal interpretations of Islam that record the highest proportional percentages when it comes to this salient metric of religiosity.

Discussion

Given the findings in relation to the religious influences highlighted above, that is, the literal interpretation of the Quran and overall religiosity through prayer, it appears that Islamism as an ideology reflects the contention of Venkatraman that ideologically preserving the “will of God” is critical and that, as Tibi noted, an Islamist derives laws not from human deliberation but from the “will of God”. This high level of religiosity among a Western sample of Muslims was again evidenced in the Rezaei and Goli sociological findings out of Denmark, where the most radical Muslims were also much more committed to religious duties “like paying Zakat and Khoms, daily prayer, participation in Juma prayer, fasting, and prayer/petition than the other groups” and also valued the words of God much higher than the words of people.58 Rezaei and Goli found that 55.6 percent of the most radical Muslims prayed daily compared to the least radical Danish Muslims at 25.7 percent. Furthermore, the most radical Danish Muslims had experienced becoming more religious in the last three years (68.3 percent) when compared to the least radical (15.9 percent); conversely, the least radical Muslims were more likely to have become less religious in the same period. Koopmans also found that the more a person identifies as religious (Muslim), the more fundamentalist and the more hostile he or she is towards out-groups.59

Tibi contends that Islamism as an ideology rests almost entirely on the notion of Islamic political order. He states: “If you want to know if a Muslim is an Islamist ask, ‘is Islam for you a faith, or is it an order of the state?’”60 that is, survey questions that tease out attitudes of personal religiosity as opposed to political order are paramount. This is a common way Islamism is defined, divorcing the religious/spiritual practice from political activism which is usually seeking an Islamic caliphate.,61 The findings from this paper suggest that Tibi’s question might have been better phrased: “Is Islam for you merely a faith or is it an order of the state?”, given that personal religiosity is higher among Islamists in the sample but also given the sources of influence more generally and conclusions drawn from many other lines of empirical evidence.

Within criminality more generally there is evidence that experiencing a traumatic life event during adolescence is a significant risk factor for subsequent violent offending and the relationship between trauma and violent offending among youth is a well-established finding across multiple high-quality longitudinal studies.62 Relatedly, a recurring theme when we examine the literature on the psychology of religion and radicalisation to extreme political and religious ideologies is a trigger event, a moment of personal crisis as a precursor to extremism and violence.63,64,65,66,67 The connection between religiosity and Islamist-jihadism is not just seen through the aforementioned sociological data; it can be evidenced through case studies of known terrorists, along with this prevalence of a triggering (traumatic) event.

Perhaps no incident captures this trend of personal crisis, religiosity, and radicalisation better than the case of Major Nidal Hasan, the Foot Hood jihadist who on 5 November, 2009 killed 13 people and left 32 injured. A detailed case study by Poppe outlined critical factors in Hasan’s radicalisation:

In 2001, Hasan’s mother passed away following a long battle with cancer. He moved in with her to take care of her during her illness and watching her deteriorate from disease profoundly impacted his psyche. Although Hasan was raised as primarily culturally Muslim rather than religiously devout, after her death, he began to worry about the state of her soul in the afterlife. According to one of Hasan’s letters, his mother had only started to become religious in the last years of her life, and he was worried that it would not be enough to earn her a place in heaven. Hasan’s parents owned a convenience store that sold alcohol, which Hasan came to believe as forbidden by Islam. The sin of selling alcohol would, in Hasan’s mind, damn his mother to an eternity of burning in hell. This religious interpretation was one he believed to be entirely literal – his mother would spend an eternity burning in a pit of fire. Hasan felt that there was a way for him to help his mother and prevent her from suffering this terrible fate. Her sins, as he saw them, could be outweighed by good actions he did on her behalf. Thus, good deeds and actions as a devout, pious Muslim could gain him a sort of “religious karma” that could be spent on erasing his mother’s earthly sins. The fear of his mother suffering this terrible fate is what sparked Hasan’s period of “religious intensification.” During this period, Hasan was not yet radicalized but was exploring his religion and beginning to place it in a more prominent position in his life.68

We can see the significant shift in worldview following the death of a loved one in Hasan’s case. The death appears to trigger an existential and metaphysical crisis that exploits the religious narrative Hasan had more than likely heard all his life but did not take particularly seriously until his mother died. One of the jihadists involved in the 2019 Sri Lankan attacks, Abdul Latheef was reported to have begun to radicalise in Melbourne, Australia 10 years prior to the attacks.69 This reported beginning of Latheef’s radicalisation was preceded by the death of his father. Osama bin Laden, the former leader and founder of al-Qaeda, also experienced a profound shift in religious intensification following the death of his father as a teenager. Bergen noted how after this incident bin Laden was changed forever, he became the most pious member of the large bin Laden family, praying six times per day (as opposed to five, as usually the practice within Islam) and attempted to strictly model every aspect of his life after the prophet Muhammad – again evidence of wide application of hadith.70 We see the same theme again in the martyrdom testimonial of Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the London 7/7 bombers in 2005: “I and thousands like me are forsaking everything for what we believe. Our driving motivation doesn’t come from tangible commodities that this world has to offer. Our religion is Islam – obedience to the one true God, Allah, and following the footsteps of the final prophet and messenger Muhammad”.71 Dawson highlights various arguments against religiosity being a critical element in jihadist terrorism, including the notion that many jihadists were recent converts thereby showing their religious understanding is superficial. Dawson calls into question this idea and appears to agree with Wood that a recent adoption of Islam/Islamism in no way shows a lack of piety. Furthermore, the “Islam in Australia” survey findings of educational interest of Muslim Australians during high school shows a statistically significant relationship between an early adolescent interest in Islam and harbouring Islamist/jihadist ideas.72

Conclusion

It is not just an appeasement of the politically correct to state that a large majority of Muslim Australians do not agree with Islamist and Islamist-jihadist interpretations of Islam; it can be empirically shown within the data. These individuals should be seen as powerful allies and moderating voices in relation to the challenge of Islamism and jihadism. The problem lies with the significant minority of Muslim Australians who do agree with Islamist ideas and acquire their ideology from mainstream areas of Islamic discourse. This needs to be part of the conversation for Muslim Australians who are vehemently opposed to illiberal interpretations of Islam and those charged with implementing counterterrorism and countering violent extremism policies and programs. A liberal democratic state such as Australia cannot have policies or programs that actively challenge one’s spirituality/religion nor should it, in more autocratic Muslim majority countries; however, this restriction is absent.73 The challenge for the Australian Muslim community, state police services, the Australian Federal Police, and Australia’s Living Safe Together program, is how can we divorce the individual from Islamist and jihadist interpretations of Islam when this connection is so strongly aligned to their idea of a pious Muslim? What we do know is that a triggering event, often surrounded by death of a loved one or death anxiety more generally, in the radicalisation process, should highlight secular grief counselling as paramount, as part of the suite of intervention methods that already help to prevent radicalisation.

Gaining a better understanding of how Islamists claim to know what they know, their belief formation, is crucial if any attempt is to be made to moderate more extreme or literal interpretations of Islam that lead to political/religious violence. This paper attempted to make steps in that direction by using data collected within the “Islam in Australia” survey which asked questions in relation to typologies of Muslims, sources of Islamic influence, literal interpretation of doctrine, and personal religiosity.

What the findings in this paper suggest is that those who agreed or strongly agreed with the Political Islamist and Militant typologies are more likely to:

- Have been influenced by mainstream areas of Islamic knowledge and discourse, such as the Quran, hadith, ulema, and the mosque.

- Interpret the Quran literally.

- Pray daily.

In some ways these findings are uncomfortable for those attempting to work with Muslim communities in order to mitigate extremism, particularly due to the fact the majority of Muslim Australians are not subscribing to an Islamist or jihadist worldview. However, these findings suggest that those charged with investigating terrorism offences or countering violent extremism more generally, should take religiosity or what may be perceived as hyper-religiosity seriously when monitoring or intervening in cases. This factor may be very relevant when an individual turns towards extremism (Islamism) or violent extremism (jihadism/militancy) and should give us pause if an individual is referred to a religious mentor or counsellor in a context of countering violent extremism.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

| 1 | Krueger, A. B. (2018). What Makes a Terrorist: Economics and the Roots of Terrorism. Princeton University Press. |

| 2 | ASIO Annual Report 2019–2020 (2020). Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (p. 17). Retrieved from link to this article. Retrieved 6/09/2021. |

| 3 | Dawson, L. (2021). Bringing religiosity back in (p. 2). Perspectives on Terrorism, 15(2), 2–22. |

| 4 | Schmid, A. P. (2013). Radicalisation, de-radicalisation, counter-radicalisation: A conceptual discussion and literature review. ICCT Research Paper, 97, 22. |

| 5 | Bokhari. L (2009) Radicalisation and the case for Pakistan: A way forward. In T. M. Pick, A. Speckhard, & B. Jacuch, B. Eds. Home-Grown Terrorism: Understanding and Addressing the Root Causes of Radicalisation among Groups with an Immigrant Heritage in Europe. Vol. 60. Ios Press. |

| 6 | Mandel. D. R. (2009) Radicalization: What does it mean? (p. 111). In T. M. Pick, A. Speckhard, & B. Jacuch, B. Eds. Home-Grown Terrorism: Understanding and Addressing the Root Causes of Radicalisation among Groups with an Immigrant Heritage in Europe. Vol. 60. Ios Press. |

| 7 | Precht, T. (2007). Home grown terrorism and Islamist radicalisation in Europe. From conversion to terrorism. In Research Report, Danish Ministry of Justice. |

| 8 | Dawson (2021), p. 12. |

| 9 | Moghaddam, F. M. (2005). The staircase to terrorism: A psychological exploration. American Psychologist, 60(2), 161. |

| 10 | Wiktorowicz, Q. (2005). Radical Islam Rising: Muslim Extremism in the West. Rowman & Littlefield. |

| 11 | Sageman, M. (2008). Leaderless Jihad. University of Pennsylvania Press. |

| 12 | Crone, M. (2016). Radicalization revisited: Violence, politics and the skills of the body. International Affairs, 92(3), 587–604. |

| 13 | Dawson (2021), p. 13. |

| 14 | Satterley, S., Rane, H., & Rahimullah, R. H. (2023). Fields of educational interest and an Islamist orientation in Australia. Terrorism and Political Violence, 35(3), 694–711. |

| 15 | Gambetta, D., & Hertog, S. (2017). Engineers of Jihad. Princeton University Press. |

| 16 | Haidt, J. (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Vintage. |

| 17 | Jones, J. (2008). Blood that Cries out from the Earth: The Psychology of Religious Terrorism. Oxford University Press. |

| 18 | Wood, G. (2019). The Way of the Strangers: Encounters with the Islamic State. Random House Trade Paperbacks. |

| 19 | Harris, S. (2005). The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason. W.W. Norton & Company. |

| 20 | Ballen, K. (2011). Terrorists in Love: The Real Lives of Islamic Radicals. Simon & Schuster. |

| 21 | Rane, H., Duderija, A., Rahimullah, R. H., Mitchell, P., Mamone, J., & Satterley, S. (2020). Islam in Australia: A national survey of Muslim Australian citizens and permanent residents. Religions, 11(8), 419. |

| 22 | See original publication (see note 21 above) for a full break down of representativeness. |

| 23 | Rane, H., & Duderija, A. (2021). Muslim typologies in Australia: Findings of a national survey. Contemporary Islam, 15(3), 309–335. |

| 24 | This paper uses the terms jihadist, Islamist-jihadist, and Militant as synonyms which all include the ideology of Islamism – the wish to impose any version of Islam over the rest of society. It is recognised that the term “Militant” could have been replaced with “Jihadist” or something analogous; holding this view, of course, did not make our participants a violent insurgent but merely showed a tendency for this worldview. |

| 25 | Martin, R., & Barzegar, A. (Eds.). (2010). Islamism: Contested Perspectives on Political Islam. Stanford University Press. |

| 26 | Mozaffari, M. (2007). What is Islamism? History and definition of a concept. (p. 22). Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, 8(1), 17–33. |

| 27 | Fattah, M. A. (2006). Democratic Values in the Muslim World. Lynne Rienner Publishers. |

| 28 | Duderija, A., & Rane, H. (2019). Islam and Muslims in the West. Palgrave Macmillan. |

| 29 | Mozaffari (2007), p. 22. |

| 30 | Gerring, J. (1997). Ideology: A definitional analysis. Political Research Quarterly, 50(4), 957–994. |

| 31 | Mozaffari (2007), p. 22. |

| 32 | Ibid, p. 22. |

| 33 | Note that the data are slightly different to Rane & Duderija (2021) as this analysis includes those that agreed with the typology question not merely those that strongly agreed. |

| 34 | Nesser, P. (2018). Islamist Terrorism in Europe. Oxford University Press. |

| 35 | McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2008). Mechanisms of political radicalization: Pathways toward terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 20(3), 415–433. |

| 36 | Shanahan, R. (2020). Typology of terror: The backgrounds of Australian jihadis. Australasian Policing, 12(1), 32–38. |

| 37 | Dawson, L. L. (2009). The study of new religious movements and the radicalization of home-grown terrorists: Opening a dialogue. Terrorism and Political Violence, 22(1), 1–21. |

| 38 | Kepel, G. (2002). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. Harvard University Press. |

| 39 | Fuller, G. E. (2003). The future of political Islam (pp. 193–213). In The Future of Political Islam. Palgrave Macmillan. |

| 40 | Tibi, B. (2012). Islamism and Islam. Yale University Press. |

| 41 | Shanahan (2020). |

| 42 | Kepel (2002). |

| 43 | Rose, M. (2015). Immunising the mind: How can education reform contribute to neutralising violent extremism. British Council. link to this article. |

| 44 | United Nations Development Programme (Gambia). (2003). The Gambia Human Development Report (p. 53). UNDP. Retrieved 8/8/21. |

| 45 | Rezaei, S., & Goli, M. (2010). House of War: Islamic Radicalisation in Denmark. Centre for Studies in Islamism and Radicalization (CIR), Aarhus University. |

| 46 | Fuller (2003). |

| 47 | Boutz, J., Benninger, H., & Lancaster, A. (2019). Exploiting the prophet's authority: How Islamic State propaganda uses hadith quotation to assert legitimacy. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 42(11), 972–996. |

| 48 | Williams, J. A. (Ed.). (1994). The Word of Islam. University of Texas Press. |

| 49 | Sageman, M. (2008). The next generation of terror. Foreign Policy, (165), 37. |

| 50 | Stevens, T., & Neumann, P. R. (2009). Countering online radicalisation: A strategy for action. International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence. |

| 51 | Conway, M., & McInerney, L. (2008). Jihadi video and auto-radicalisation: Evidence from an exploratory YouTube study (pp. 108–118). In Intelligence and Security Informatic. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. |

| 52 | Commins, D. (2005). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. Bloomsbury Publishing. |

| 53 | Venkatraman, A. (2007). Religious basis for Islamic terrorism: The Quran and its interpretations (p. 229). Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 30(3), 229–248. |

| 54 | Argyle, M. (2005). Psychology and Religion: An Introduction (p. 111). Routledge. |

| 55 | Danaher, J. (2019). In defence of the epistemological objection to divine command theory (p. 382). Sophia, 58(3), 381–400. |

| 56 | Note that the original source only included “strongly agree” giving slightly different data but the same sociological trend. |

| 57 | Rane & Duderija (2021). |

| 58 | Rezaei and Goli (2010), p. 123. |

| 59 | Koopmans, R. (2015). Religious fundamentalism and hostility against out-groups: A comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(1), 33–57. |

| 60 | Tibi (2012), p. 31. |

| 61 | Mozaffari (2007). |

| 62 | Peltonen, K., Ellonen, N., Pitkänen, J., Aaltonen, M., & Martikainen, P. (2020). Trauma and violent offending among adolescents: a birth cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health, 74(10), 845–850. |

| 63 | Borum, R. (2011). Radicalization into violent extremism I: A review of social science theories. Journal of strategic security, 4(4), 7–36. |

| 64 | Silber, M. D., Bhatt, A., & Analysts, S. I. (2007). Radicalization in the West: The homegrown threat (pp. 1–90). New York: Police Department. |

| 65 | Aly, A., & Striegher, J. L. (2012). Examining the role of religion in radicalization to violent Islamist extremism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 35(12), 849–862. |

| 66 | Porter, L. E., & Kebbell, M. R. (2011). Radicalization in Australia: Examining Australia's convicted terrorists. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 18(2), 212–231. |

| 67 | Rambo, L. R. (1993). Understanding religious conversion. Yale University Press. |

| 68 | Poppe, K. (2018). Nidal Hasan: A case study in lone-actor terrorism (p. 6). George Washington University. |

| 69 | Palin, M. (2019, April 26) Sri Lanka bomber ‘radicalised in Australia’, says sister. Retrieved from link to this article. Retrieved 5/10/21. |

| 70 | Bergen, P. (2021) The Rise and Fall of Osama bin Laden. Simon & Schuster. |

| 71 | Dawson (2021), p. 1. |

| 72 | Satterley & Rane (2021). |

| 73 | Rabasa, A., Pettyjohn, S. L., Ghez, J. J., & Boucek, C. (2010). Deradicalizing Islamist Extremists. National Security Research Division, RAND Corp. |

© 2024 Copyright by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).